Possum Head Hollow

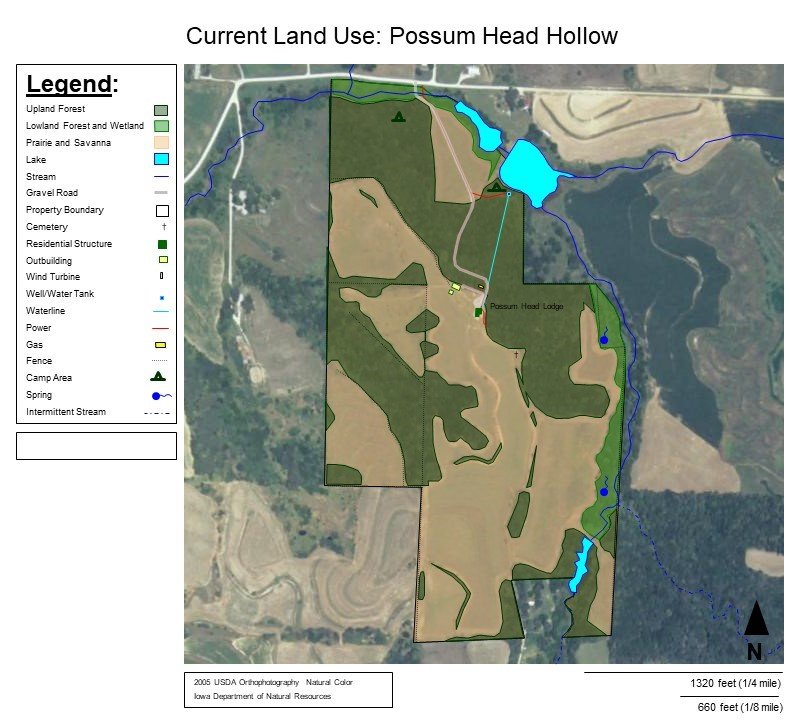

Together with my father - a certified professional engineer and former Superfund Project Manager - I have been managing 110 acres of conservation land in Iowa’s Loess Hills since 1991. Beginning with planting pines that first year, we spent the last 34 years learning about ecological restoration through observation, experimentation, documentation, and reapplication.

At Possum Head Hollow I also gained valuable experience working with various government contracts, such as Conservation Reserve Program, and received technical and direct assistance from USDA FSA, NRCS, Mills County Conservation Board, and The Nature Conservancy.

Just what the doctor ordered…

I have extensive experience using prescribed fire as a land management practice at Possum Head Hollow, and over two decades of observational data regarding its application in various scenarios. I also participated in prescribed fire applications in Kansas while embedded with the Grasslands Heritage Foundation, and have spent over two decades researching and making field observations at prescribed fire and wildfire locations in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado, from a disaster mitigation and ecological restoration perspective. Out of all this experience and data, I created a number of presentations and classroom assessments at the nexus of urban planning, ecological restoration, wildfire, and climate change (see my teaching portfolio for more).

Low-Impact Ecological Restoration

All of my conservation work in the Loess Hills Region, including Vincent Bluff, West Oak, and Folsom Point Preserve, led me to developing a low-impact, organic philosophy towards ecological restoration. At Possum Head Hollow we put that philosophy to work, endeavoring to use chemical herbicides and intensive mechanical methods only as last resorts. The fragile soils of the Loess Hills are very susceptible to erosion, so reducing the amount of disturbance to the soil is the most important conservation practice we can have in this particular landscape. Though it has taken longer, and required more hours of manual labor (and miles on boots and pounds on back), the results speak for themselves: several natural springs have reappeared, owing to more groundwater infiltration and less overland stormwater flow; biodiversity has benefitted, wildlife has returned, and now seeks our property out as a haven amidst a landscape of row crops, pastures, and hunting reserves; water quality has improved dramatically, allowing once-devastated wetlands to re-emerge in the Bomer Creek Watershed.

My father, Kevin, receiving the Stewardship Award from Glenn Pollock of the Loess Hills Preservation Society in 2006.