Bury Me on the Prairie

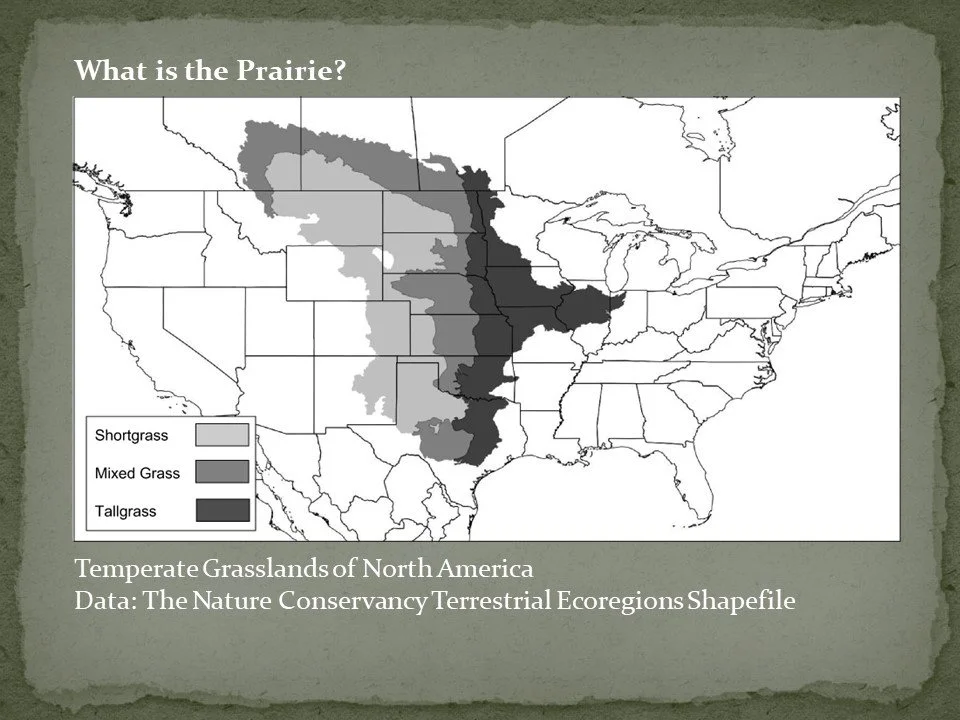

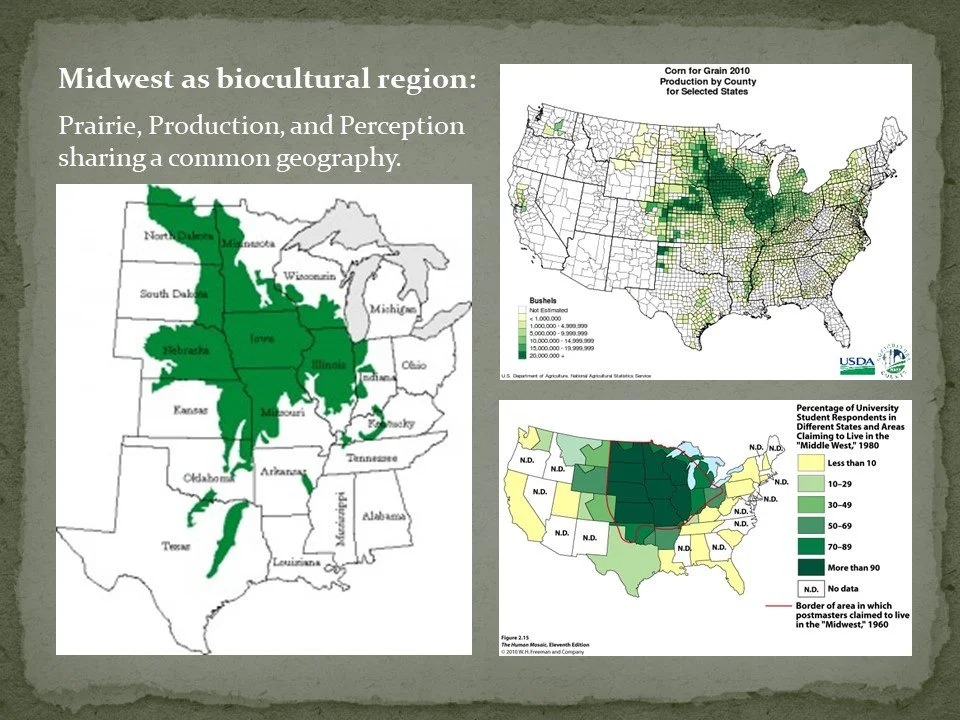

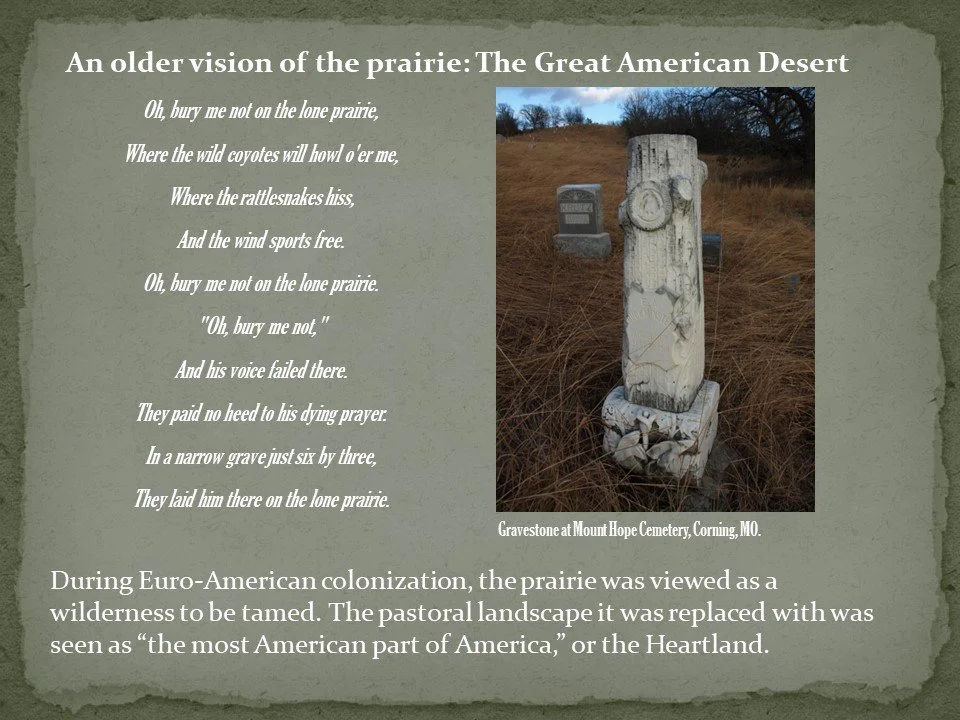

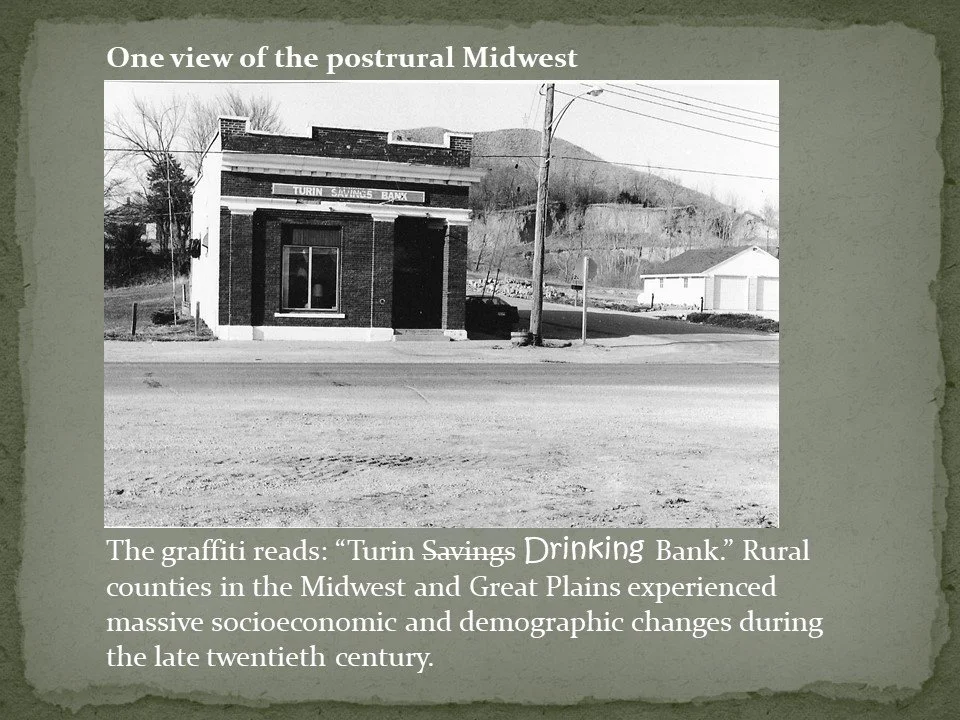

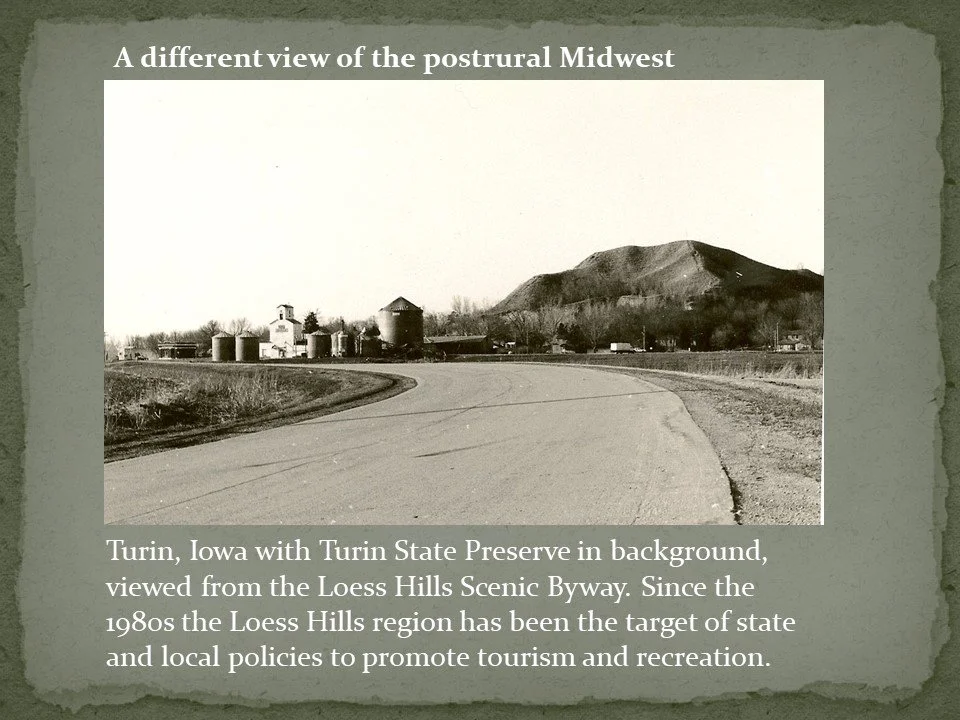

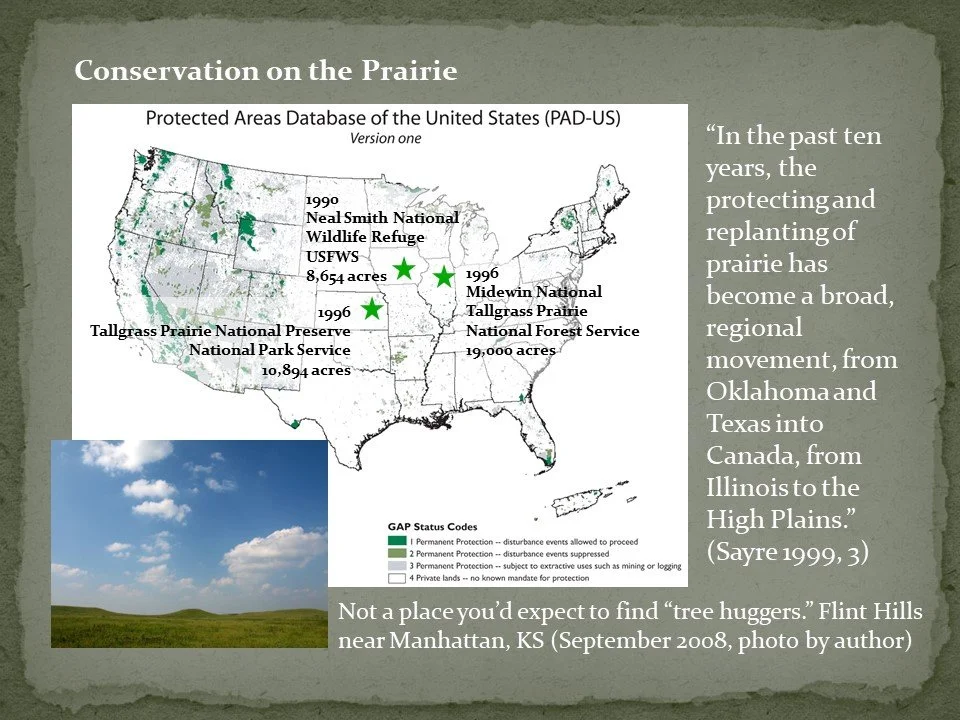

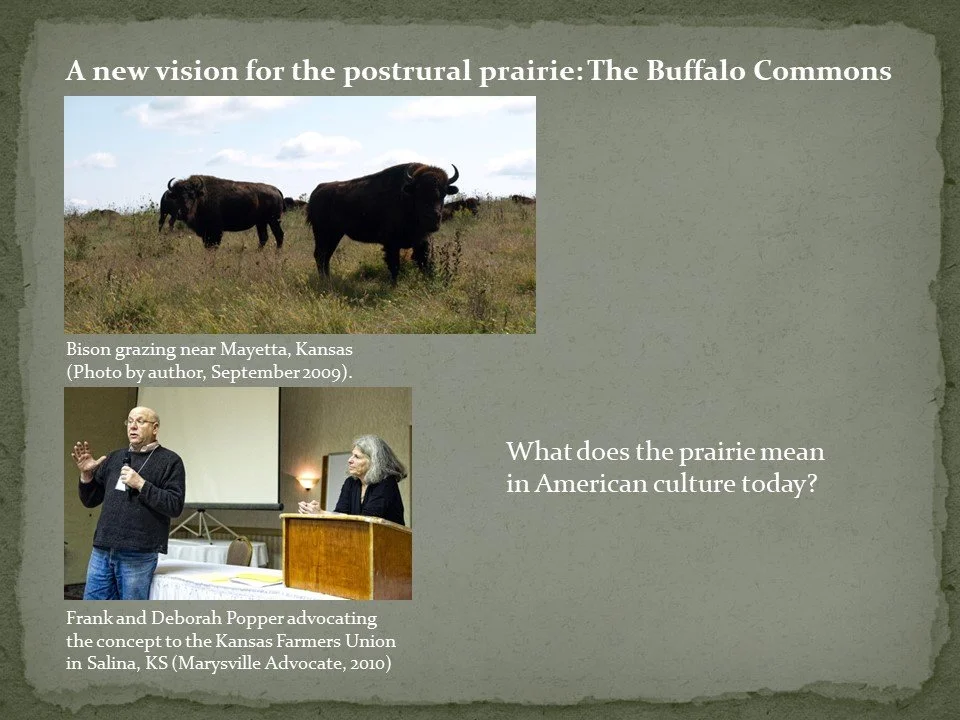

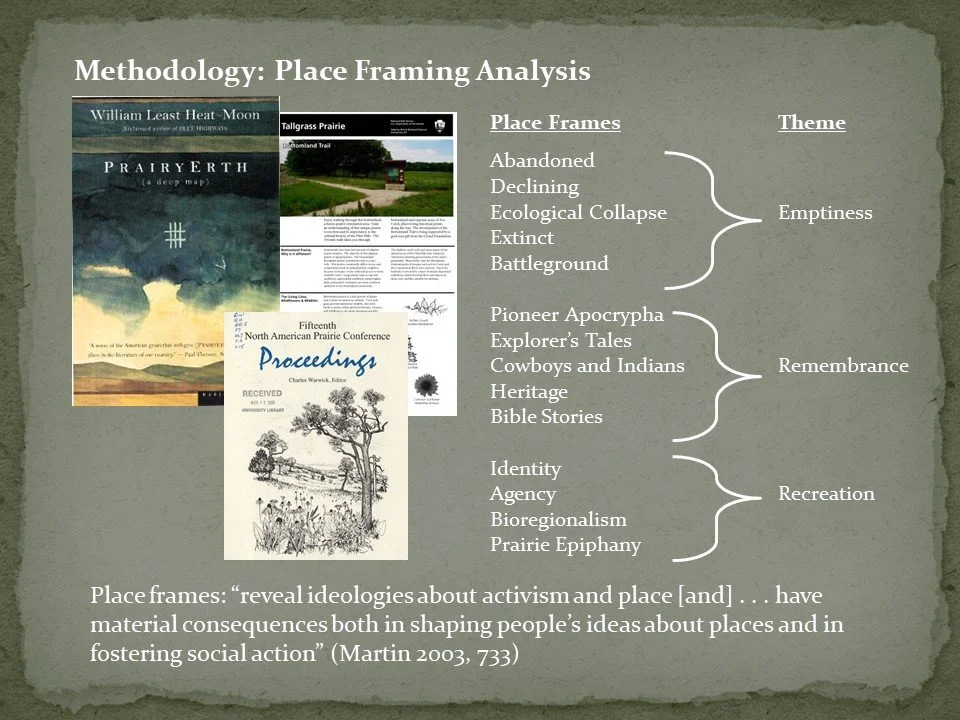

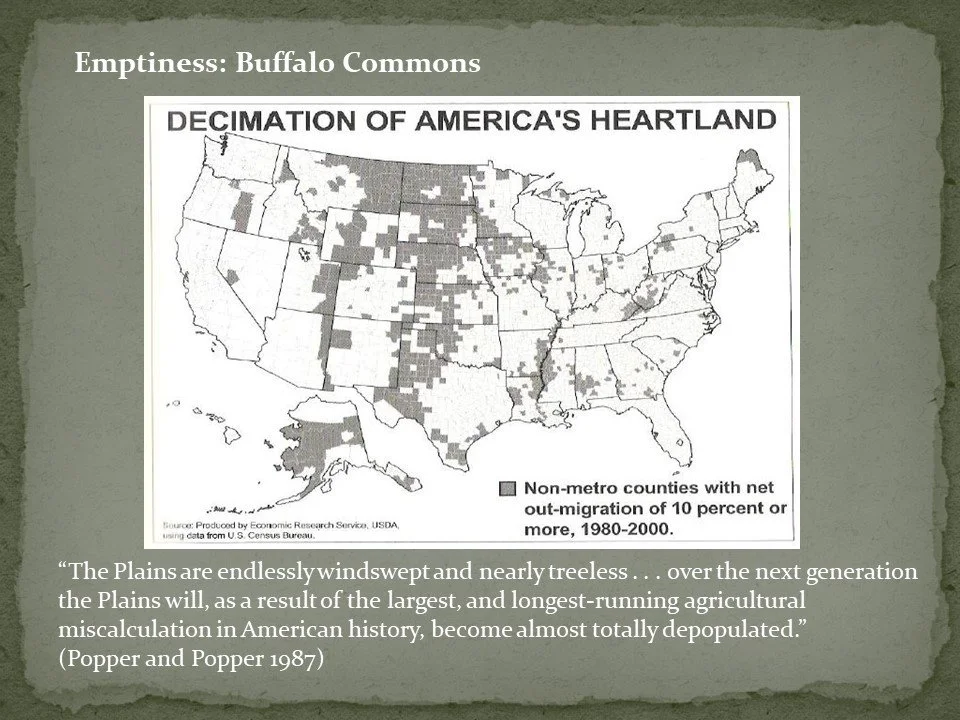

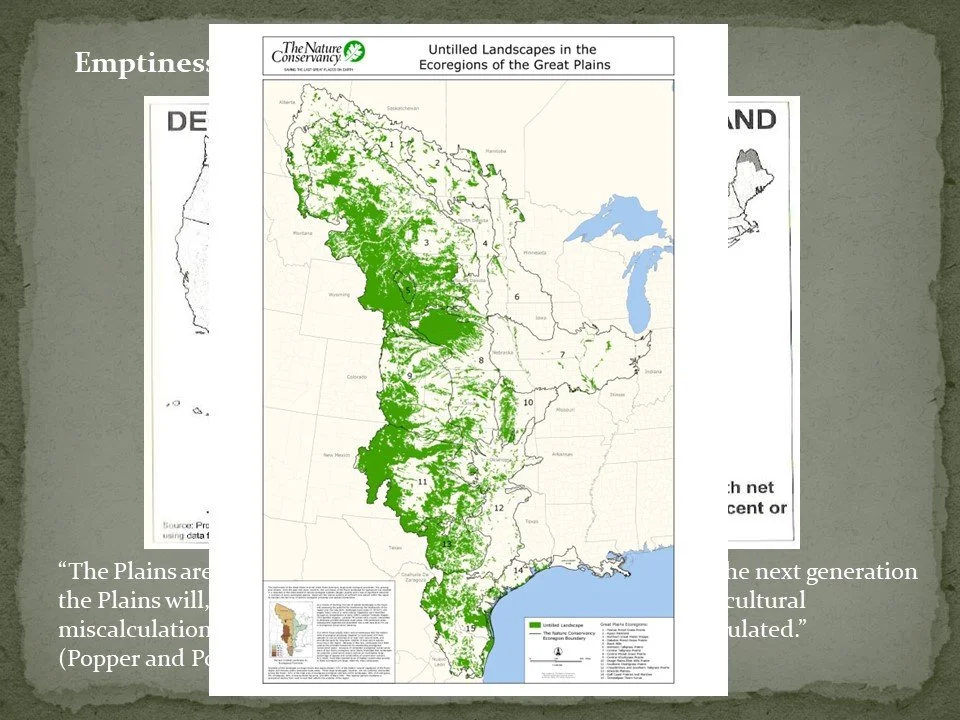

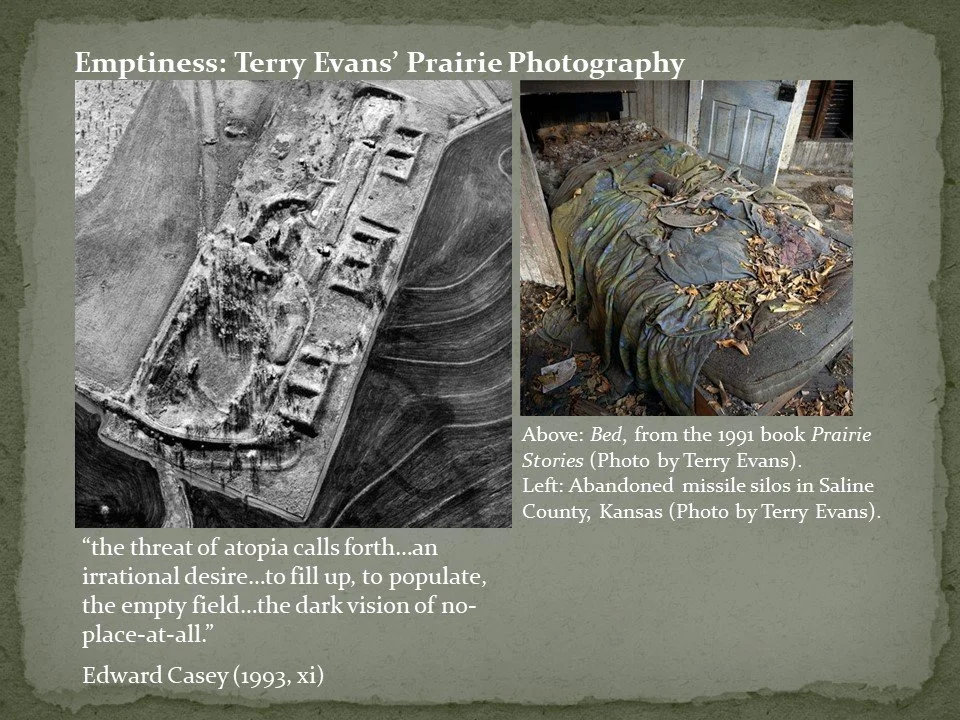

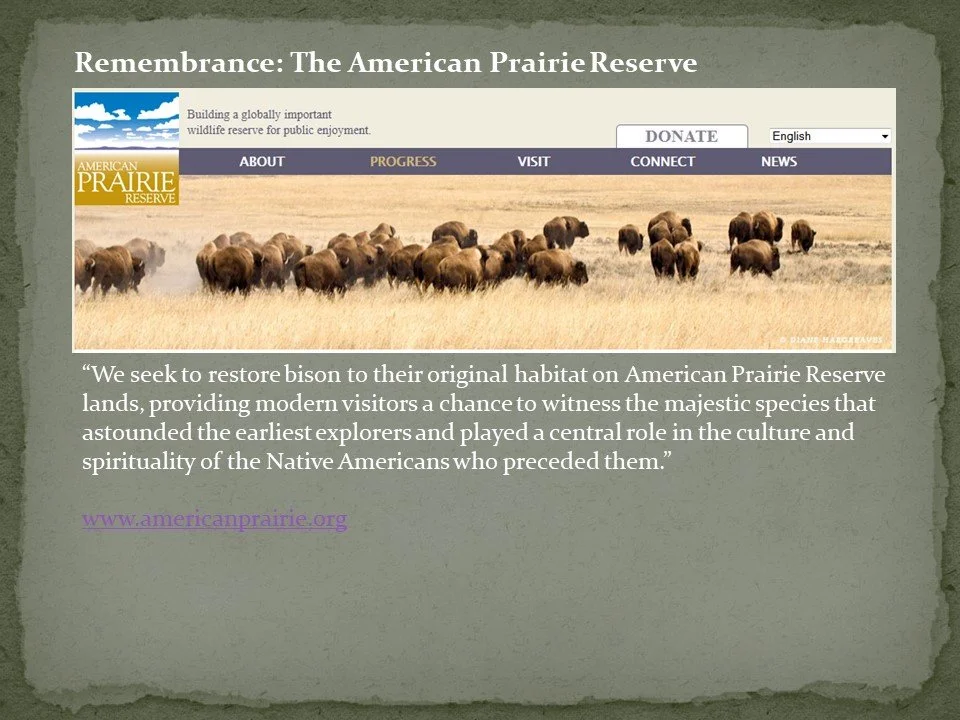

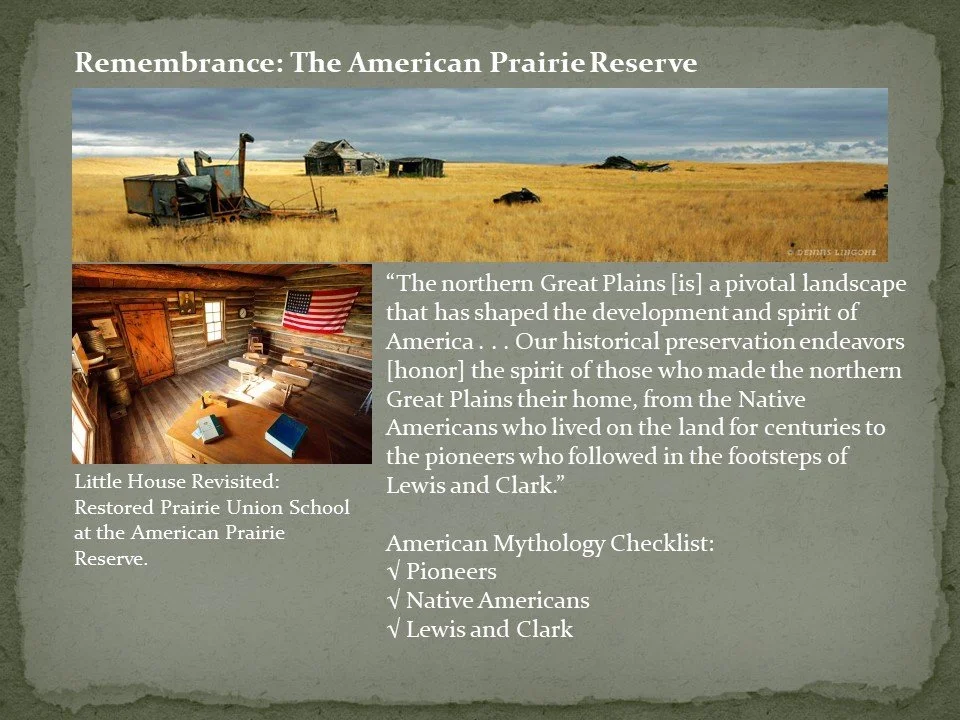

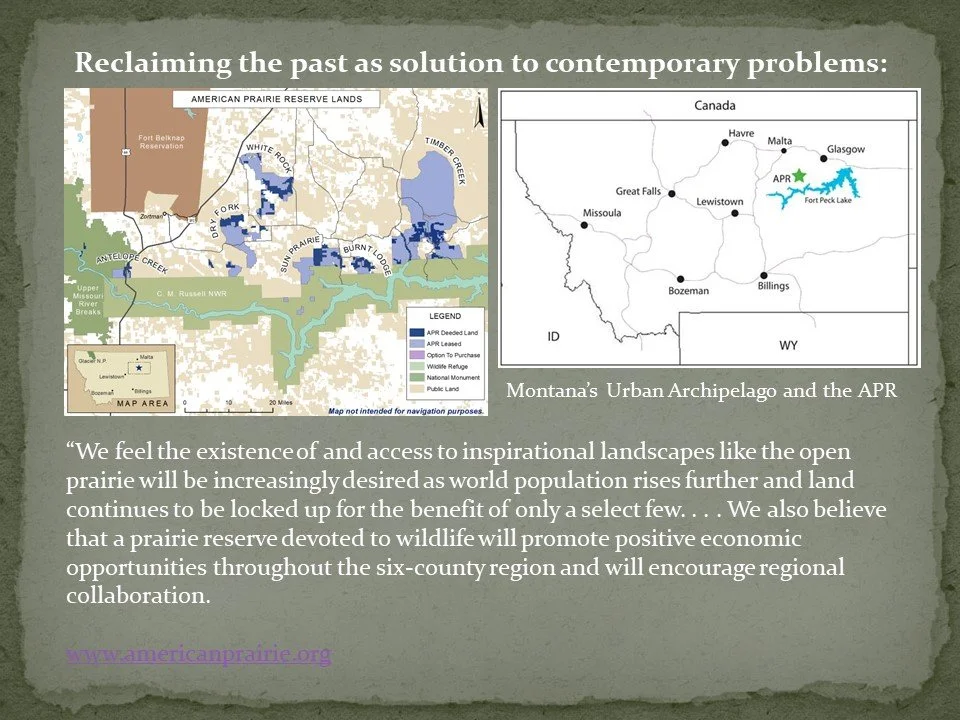

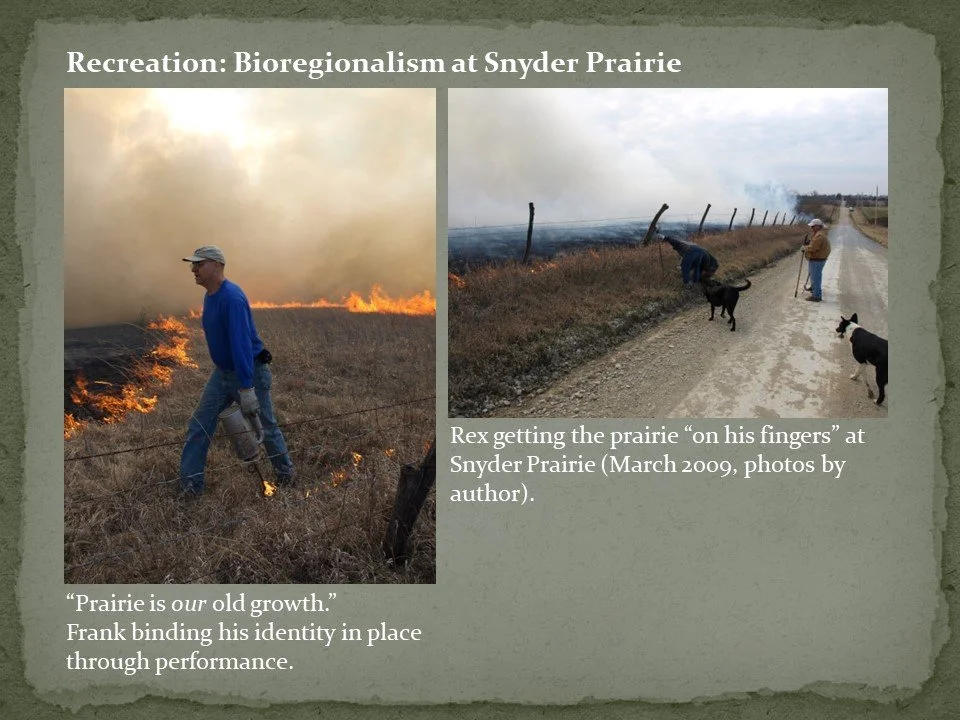

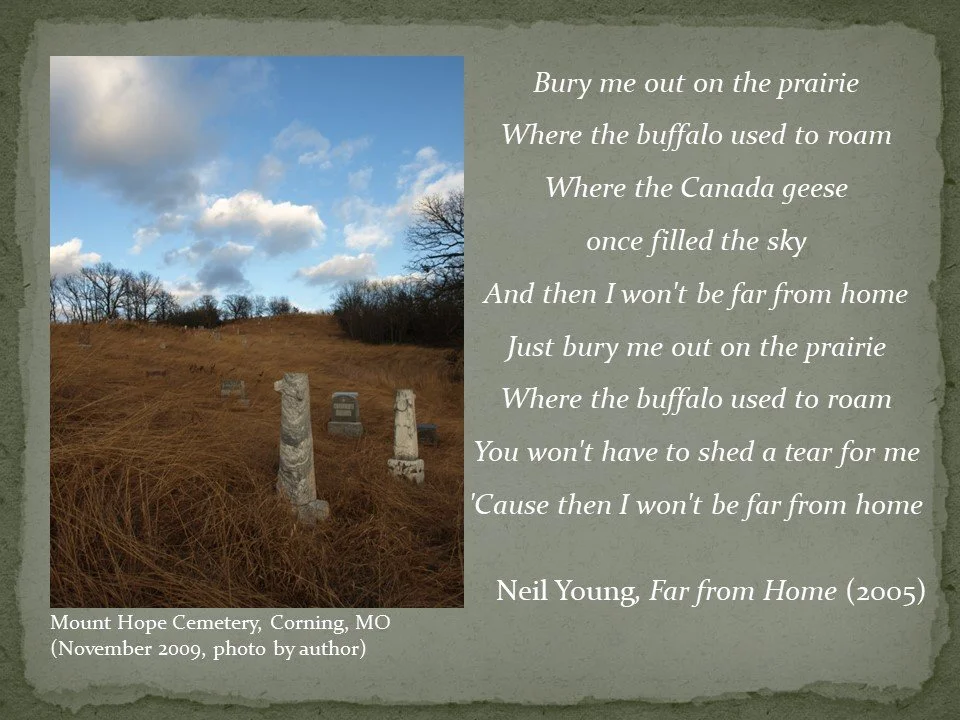

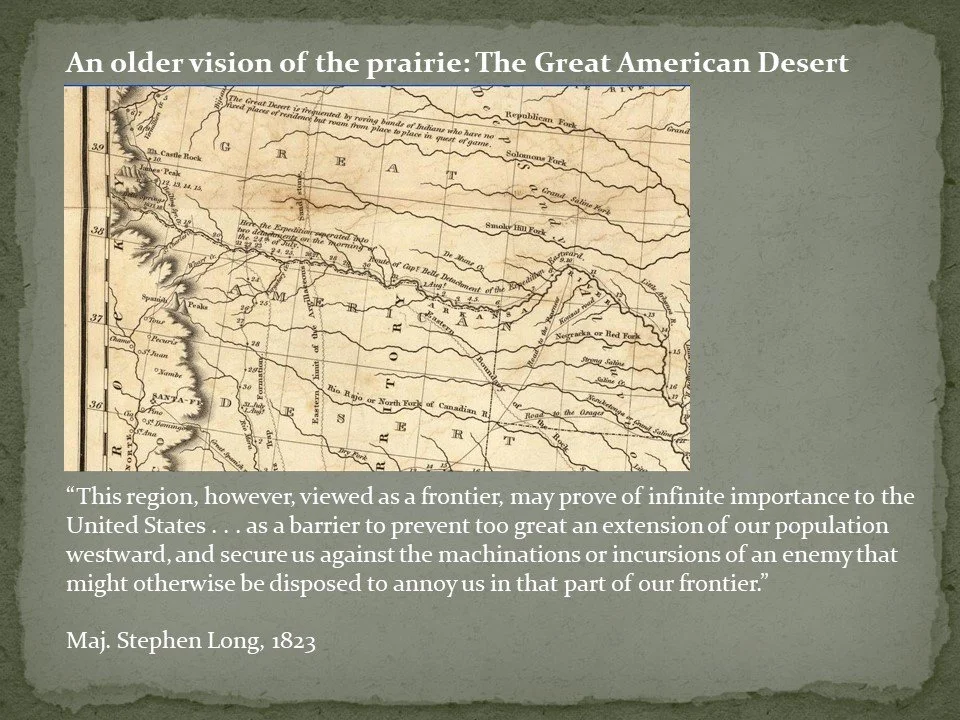

My dissertation research, published in 2014, sought answer the basic question: what does the prairie mean? Utilizing a mixed methods approach that combined enthography, participatnt observation, and critical discourse analysis, I examined how the prairie was understood, valued, utilized, and now, restored, in American culture and the popular geographic imagination. More broadly, I viewed this project as a cultural ecology of the grasslands of North America from the Pleistocene to the Present, but, dissertations being what they are, my advisors thankfully counseled me towards a more manageable goal! The results were both theoretically important, as well as applied. Firstly, through critical discourse analysis of interviews, participant observation field notes, media and scientific research regarding prairies in North America, I identified three common frames: loss, remembrance, and recreation. “Prairie People” I found, all shared a common narrative understanding of the prairei as a landscape, and a character or backdrop in American history. They also characterized the prairie in remarkably common, and temporally stable, ways. The focus on loss (“Only one percent of the original prairie remains” for example), discursively victimizes the prairie, feminizing it as a passive receiver of violence committed by American colonialism (never Indigenous practice - this is always naturalized, reducing Indigenous people and their efforts to remake the landscape to that of animals). Remembrance as a frame involves overwhelming deployment of imagery of American Manfifest Destiny, and mirrors the ethnic background of most “Prairie People” - white Euro-American settlement, wagons on the plains, farmers taming the prairie, that sort of thing. This frame appeals to the demographic of most Prairie People, which skews old and white and male, who now liviving in the postrural Midwest, primarily work in urban settings, office jobs, and pine for the romantic life connected to the land that they imagined their settler ancestors lived. Remembrance as a frame is also important because, as with other research into landscapes of remembering reveal, memory is just as much about forgetting the past, and deciding which part should be valorized, and which swept under the rug. In the case of the prairie restoration movement, it is very clear what version of history is valorized - while it receives the blame for the destruction of the prairie, White Settlement is very much the focus of the prairie restoration movement’s understanding of the landscape. Which brings the third frame - recreation - into view. The loss frame wipes the slate clean, so to speak. Remembrance allows prairie people to place themselves and their identities into the landscape, now emptied, discursively and phyusically, of it past inhabitants, and provides the justificaiton for Recreation. Recreation is meant in the original, Thoreau-ian sense of the word - to Re-Create. In the Prairie Restoration literature and discourse there is much emphasis one what the goals of prairie restoration are, and what the future of the landscape should be. Recreation as a frame represents the normative landscape of prairie people, and it is a curative for all kinds of societal ills, from climate change, to rural population loss, and even ADHD in kids! What is fascinating to me about this research, is that once revelaed, this discursive process is present everywhere! In urban planning and historical preservation, for example - I recall Robert Venturi’s lament that no one is preserving the Strip, and havce forever pondered why all historica preservation in American cities is obsessed with the Jane Jacobs aesthetic - the walkable City Beautiful. But no one thought that Pruitt-Igoe was worthy of historic preservation, despite it being more a model for the future of 20th century America than any Beaux Arts brick building in a dense walkable urban core!? What we choose to preserve, conserve, and recreate says a lot about who were are and what our values are. So, I took all of this research and presented a report to GHF and the end of my residency. Now, part of this was obviously auto-ethnography - I wanted to understand how I ended up being a prairie person. It was such a huge part of my identity, my family, and I felt part of what was clearly a wider movement, celebrating a place that I psent much of my childhood lamenting as boring. And I definitely felt the remembrance piece - my own great-great grandfather arrived in a wagon to the Loess Hills in 1847, the year after the Potawatomi Tribe was removed from the area to a reservation in Kansas, and settled on a farm not far from Chief Waubonsie’s former village site, and adjacent to the farm that my dad and I spent years restoring to presettlement condition. So it appealed to me. But, I found, that when I hung around with other young environmentalists, we didn’t have much in common. I like tractors and chainsaws and country music. And that seemed to matter to college environmentalists. I wasn’t one of them. And frankly, I didn’t vibe with the whole sign-waiving, protest, dreadlocks sort of thing. So that really got me to thinking about the cultures of environmetnalism, and, growing in a place wher eI was called a hippy tree hugger by the hillbillies, I thought - these are the real barriers to healthy ecocystems. So, through my ethnographic study, I also engaged KU student groups, such as Environs, and brought them out to the praire for restoration days. But it was important to educate the established prairie people on messaging - college students didn’t care about “imagining what it was like before white people”, and they weren’t swayed by “Amber waves of grain” imagery. And they weren’t raised with a “mother nature is precious and fragile” ideology either. These are the kids of cliamte change. Nature is powerful. Nature is a force. Nature is a female deity! So, we focused on how prairies are great carbon sinks, fonts of biodiversity, and great antidotes to climate change. Similarly, to engage with urban demographics, we could highlight how native grasses in urban setting can help combat environmental racism and improve water and air quality. But if you read literally ANYTTHING with the woird prairie in it (believec me, I did it - I literally everything int he KU library and on the entire internet with the word prairie in it!), you won’t find mention of these things. It’s all about virgin prairie being rocked by the plow by strong white men, who now, guiltily, set about fixing what they broke. I mean, it’s a classic white hero narrative! So, that is why prairie restoration is old and white. But I thought we could make it young and sexy by simply reimagining our discourse.

Dissertation Defense Presentation, October 2014

AAG Presentation, April 2013

AAG Presentation, April 2016

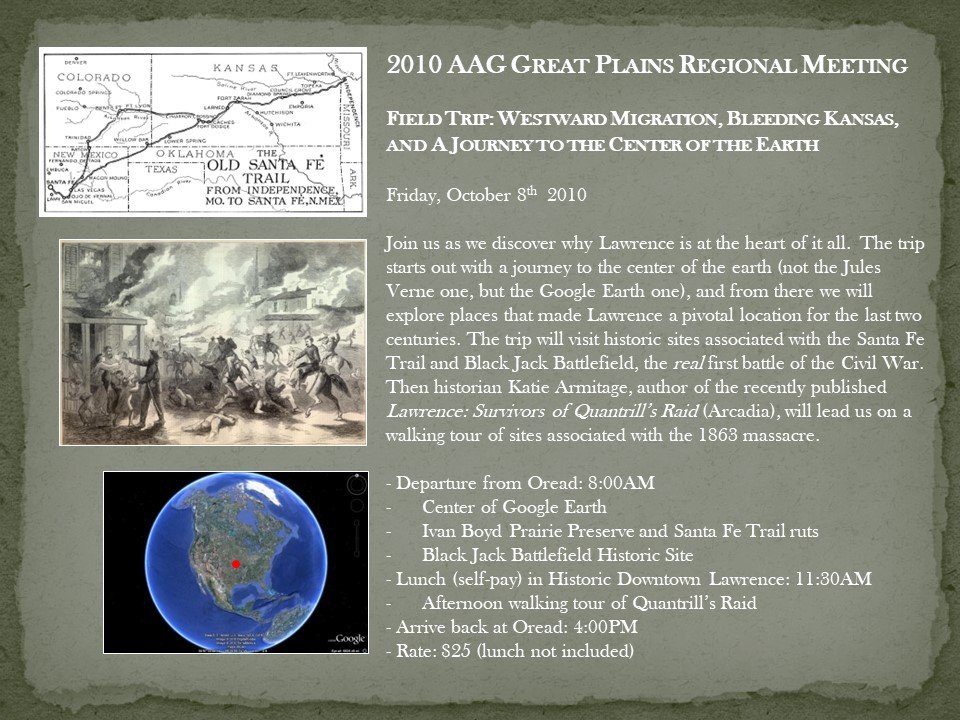

AAG GPRM Regional Meeting, October 2010

Mid-American Humanities Conference, April 2010