He is a good horse and we love him.

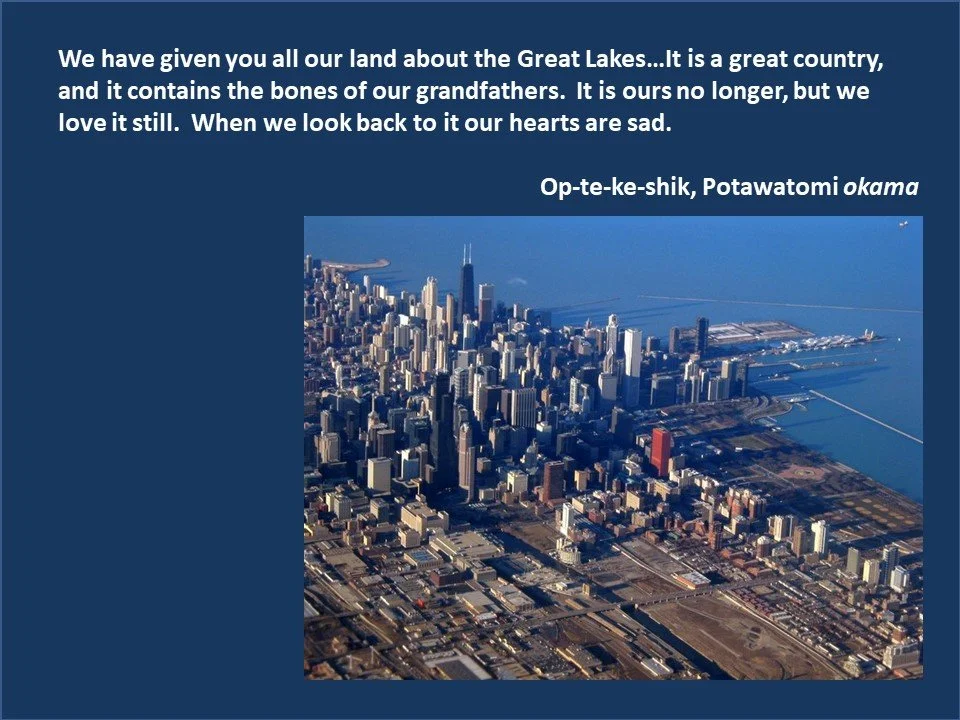

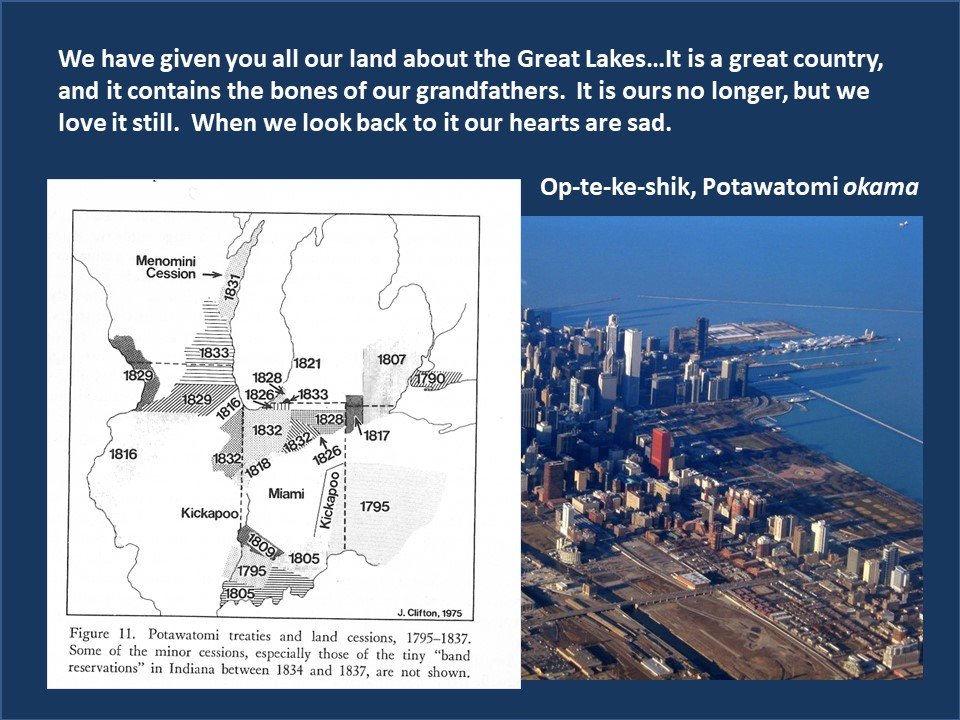

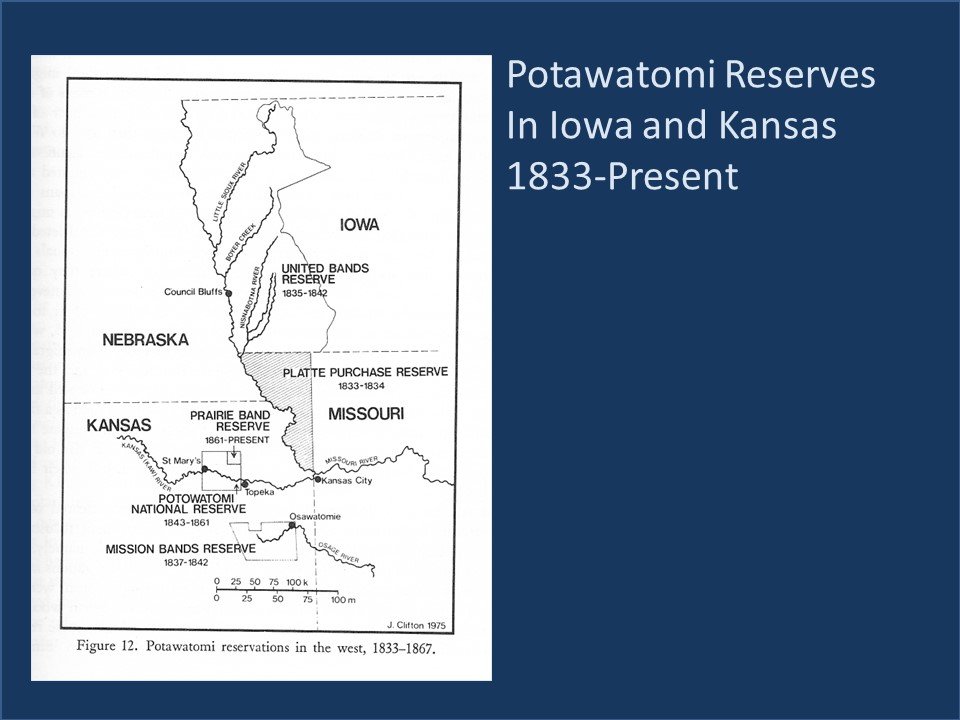

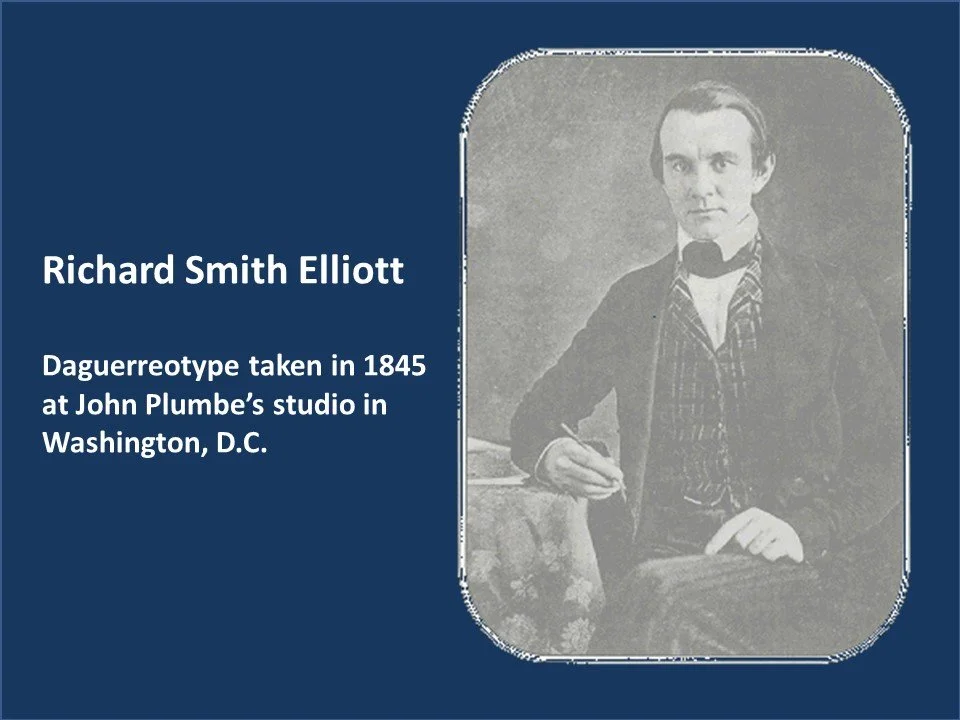

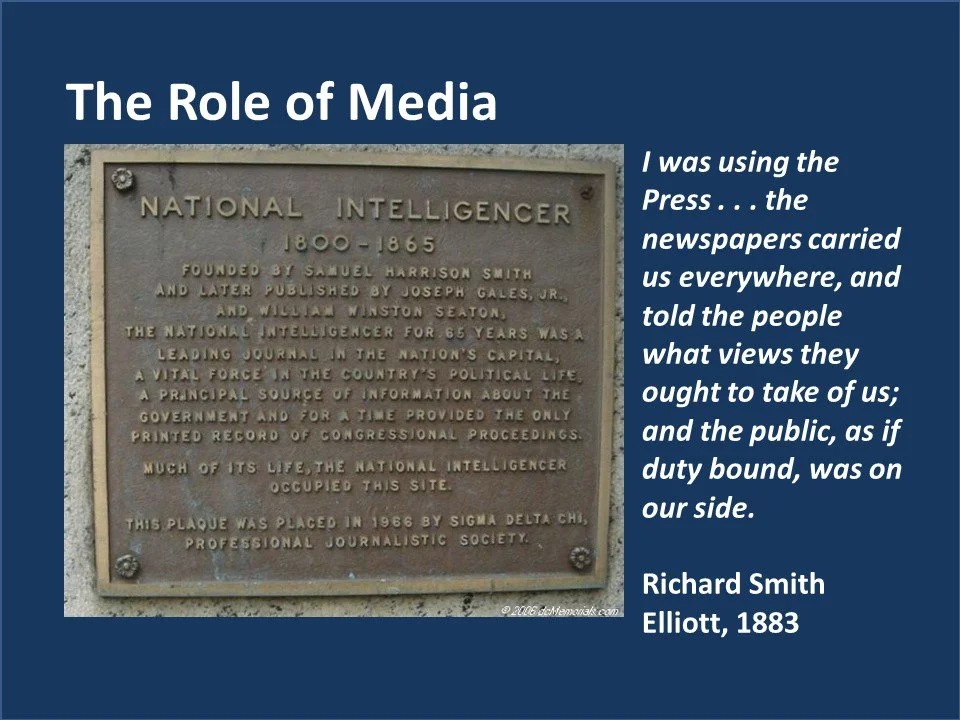

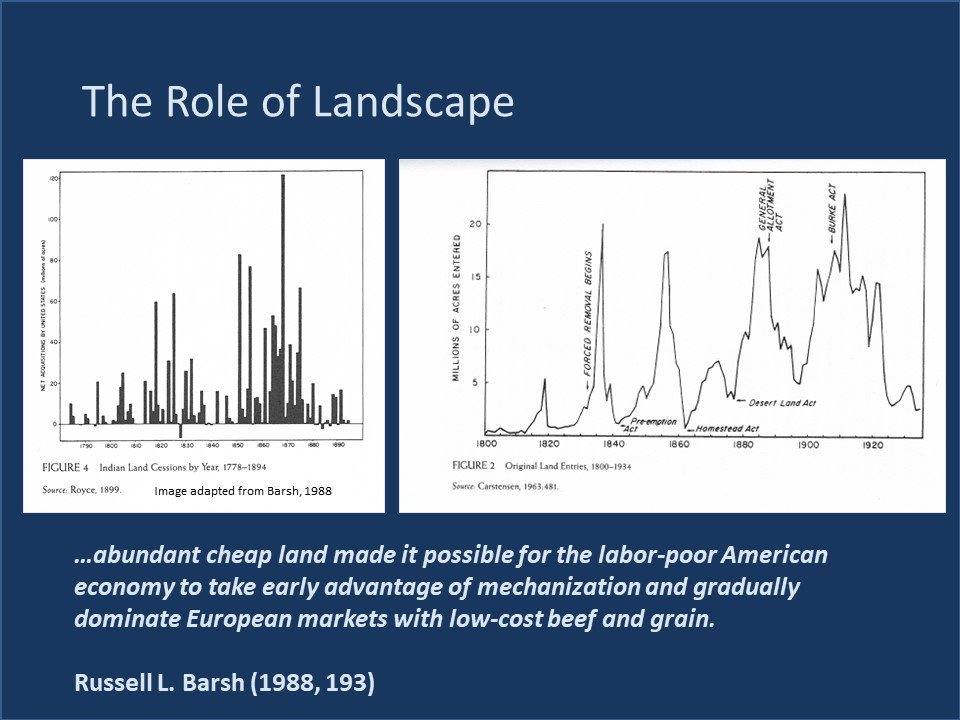

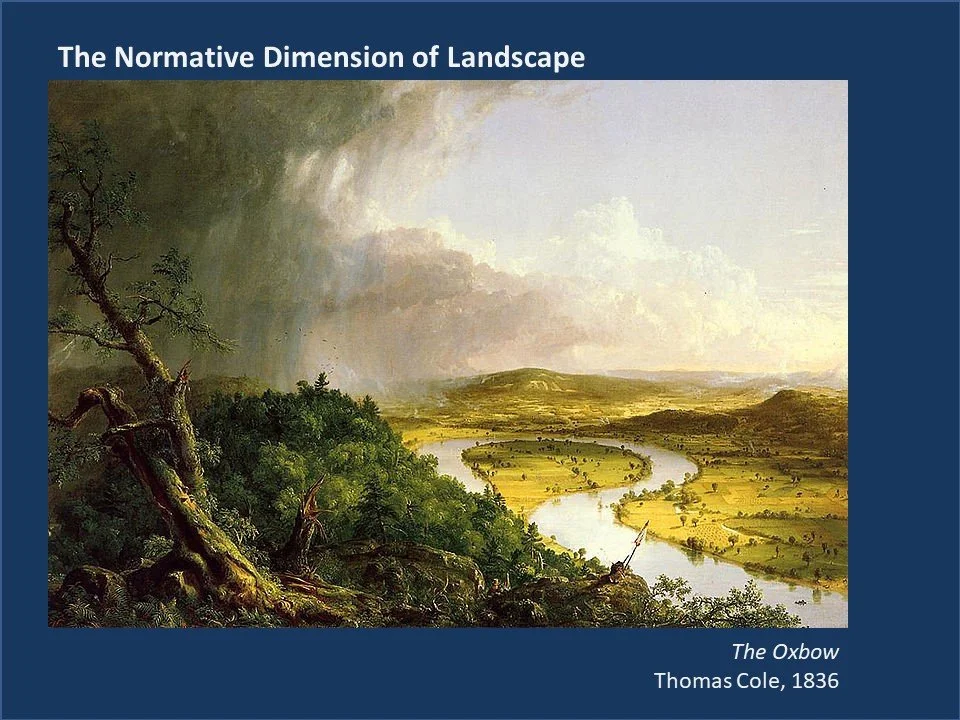

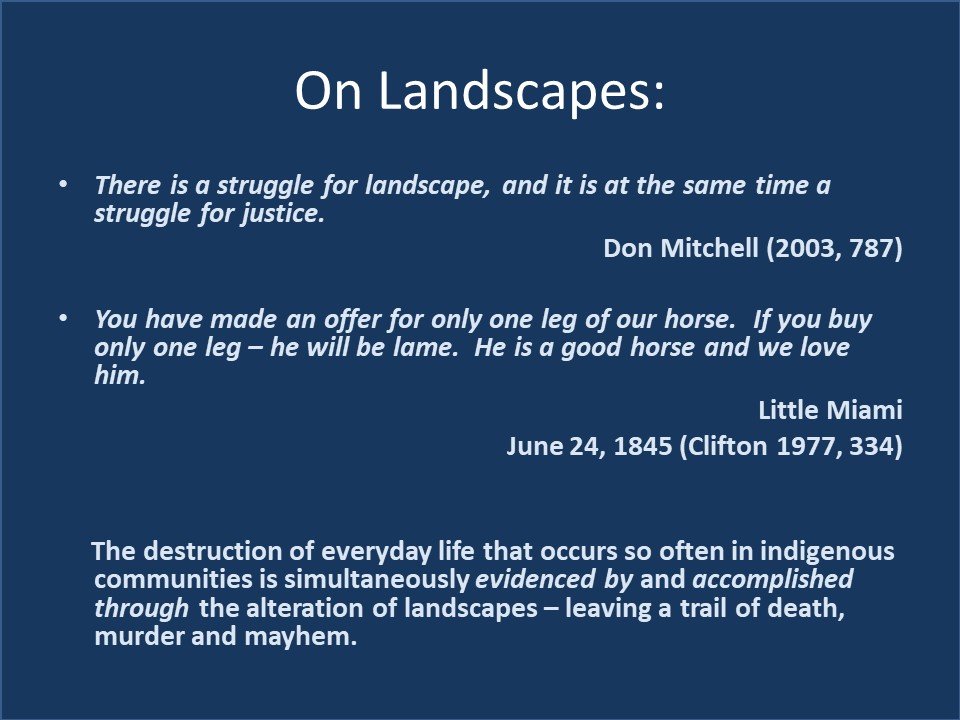

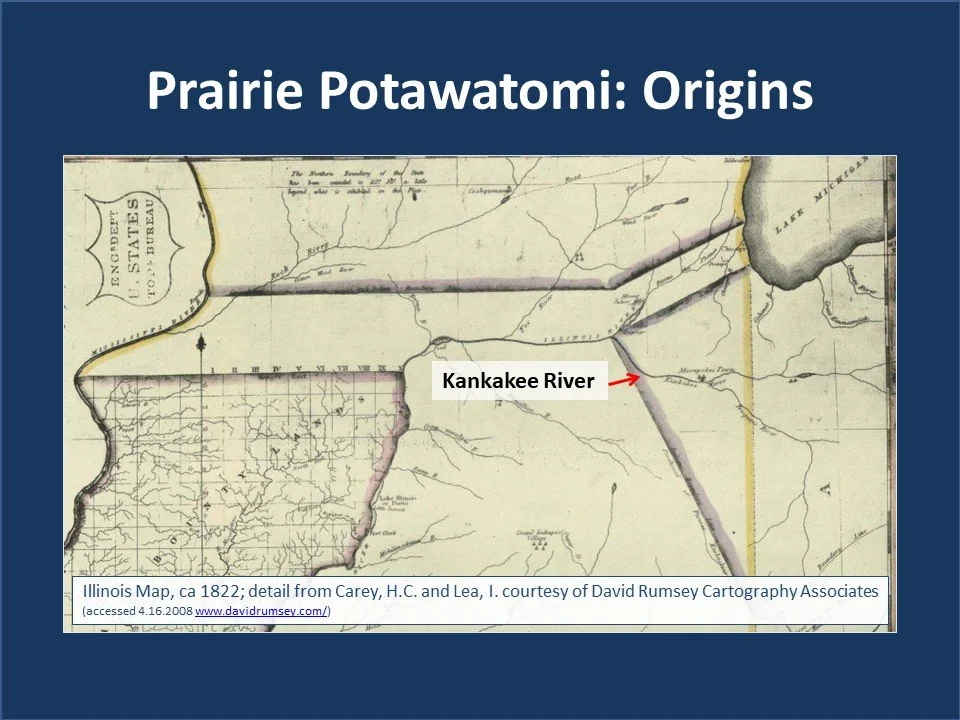

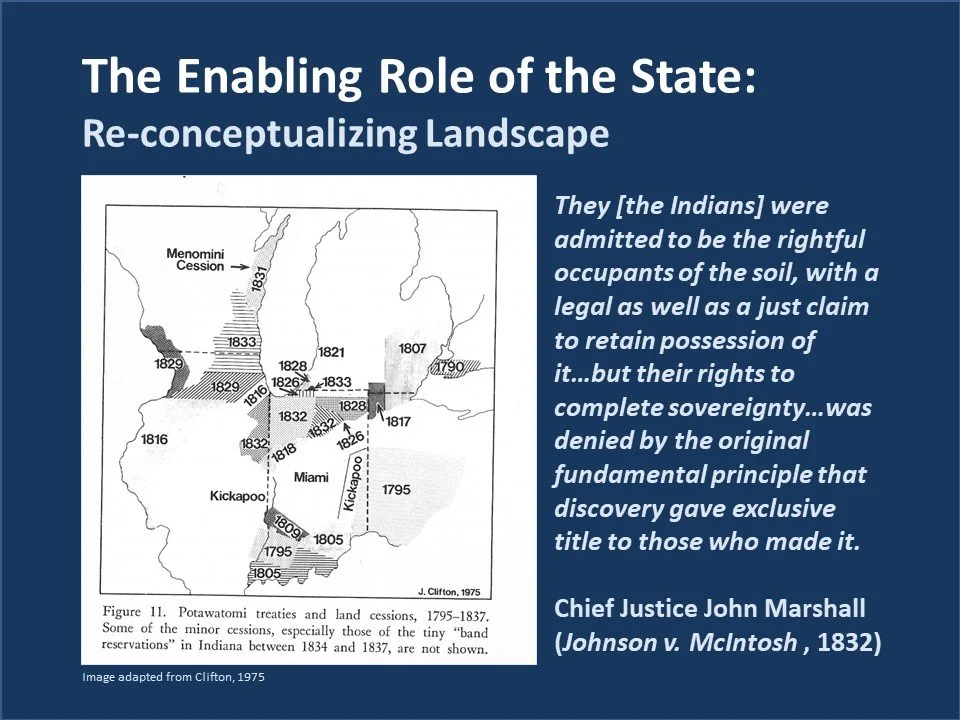

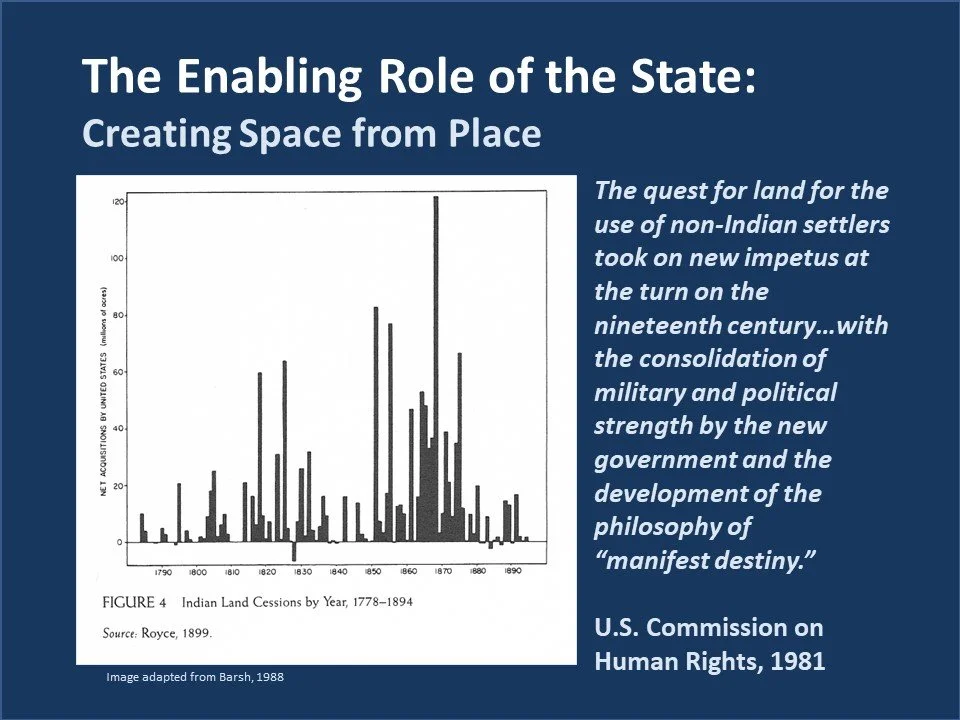

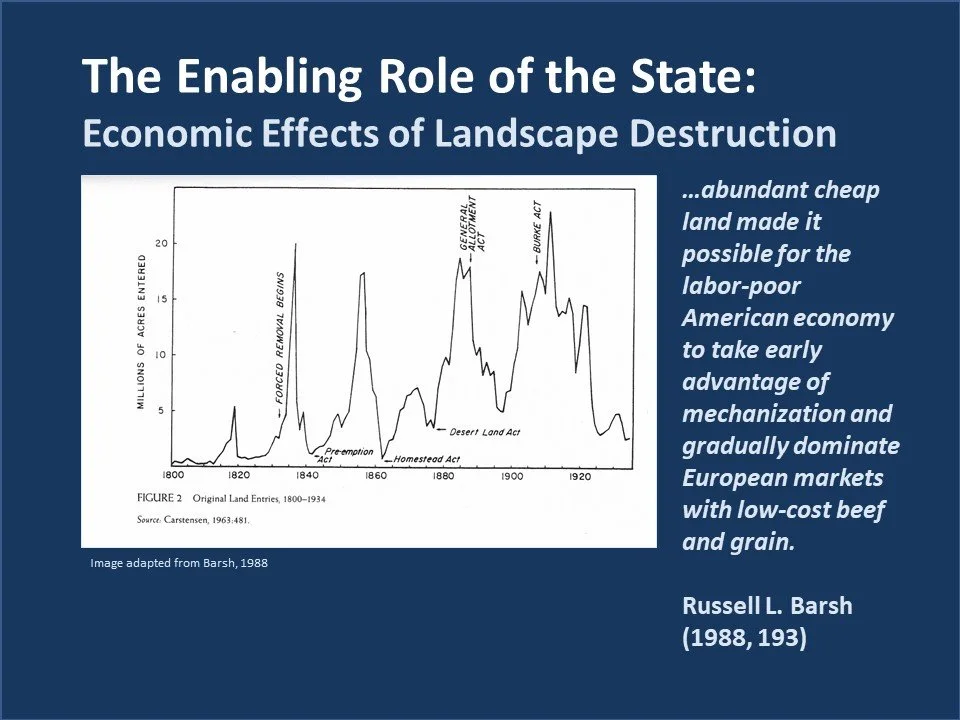

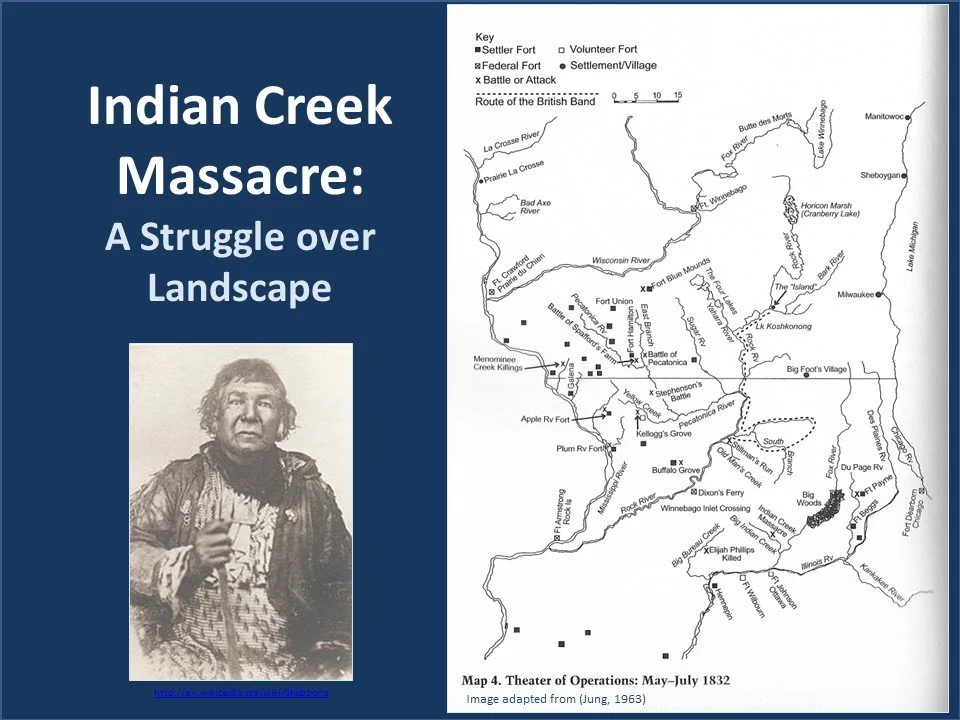

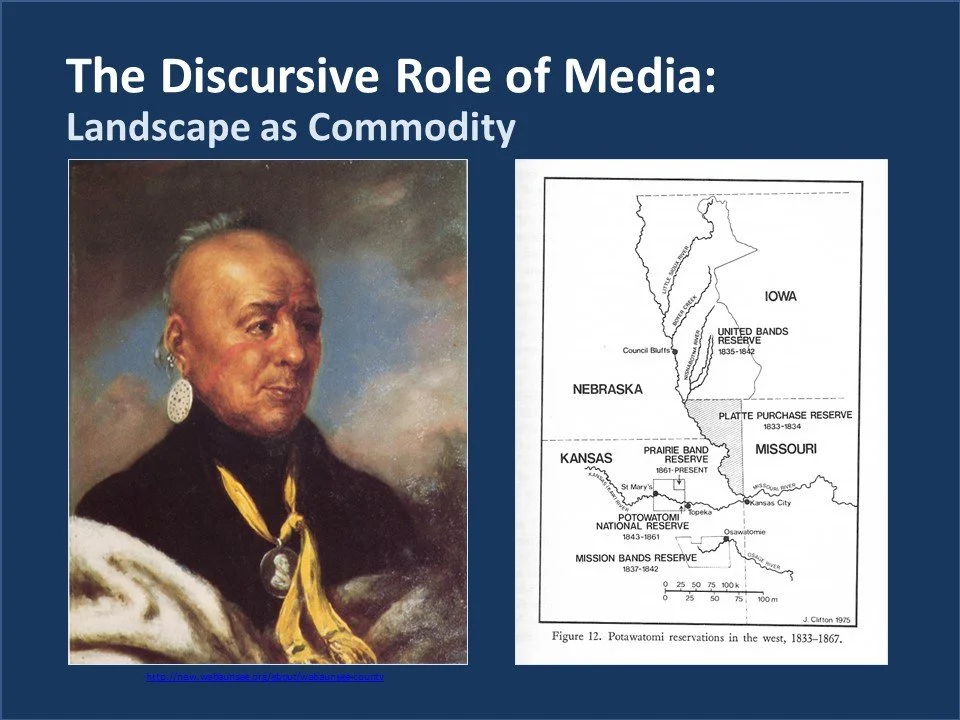

This project began with a desire to tell the story of the Potawatomi Trail of Death. All of my research into prairie restoration and ecology had been leading me back to the “settlement era.” My own family’s history is implicated in this story - my great, great grandfather James and his brother Alonzo having arrived in Iowa’s Loess Hills on the heels of the Potawatomi in the 1850s, and took homesteads not far from where my father and I were restoring prairie. I grew up with the names of Waubansie and the language of the Potawatomi on my tongue, but it wasn’t until graduate school that I began this journey deep into the history of the Loess Hills, and that led me further afield, to the homeland of Waubansie, and the journey of his people. I conducted deep historical research finding a wealth of secondary sources through library searches, including two ethnographies of the Potawatomi by Clifton (1975) and Edmunds (I would later go on to study ethnography at the University of Kansas, under Don Stoll). Synthesizing from these and other sources, I retraced a historical geography of the Potawatomi Trail of Death, and presented a paper at the Great Plains HUmanities Symposium in 2007. In 2008 I met with Jay Johnson, and eventually followed him to KU to begin my dissertation research. Jay helped me to see that the Potawatomi story, as compelling and hidden to American eyes as it remains, wasn’t mine to tell, but that there was an interesting story in here that I could follow - what was the white experience of dispossession? How did white people view this period of time? The fascinating thing about that question is that in my research on the Potawatomi, I had come across a fascinating character by the name of Richard Smtih Elliot - a character mostly lost to history, but who rivaled PT Barnum and Horace Greeley for 19th century journalistic bombasity and blurring the lines between activism, journalism, and corruption. Elliot, after spending time working as Indian Agent to the Potawatomi, was hired by the Prairie Band to aid in their negotiations with the US Government upon their third relocation from their homeland on the shores of Lake Michigan, eventually to Kansas. In this second iteration of the project, I approached this episode in history from the perspective of landscape studies, and applied the methodology of critical discourse analysis, specifically framing analysis, to understand how normative ideas of landscape presented through media coverage of the Indian Removal Act and the Potawatomi Trail of Death were essential in providing moral cover for ethnic cleansing. I outline Elliot’s role in the plight of the Potawatomi, and how media and landscape play insidious roles in justifying dispossession. The really fascinating, and unexpected thing was that I did not encounter the sort of blatant, seething racism against Indigenous people that you might think, but, rather, an overwhelming, and “woke” mentality in media coverage that seemed to provide rhetorical morality in the face of dispossession. I presented these ideas at the AAG Annual Meeting in Washington, DC in 2009, winning the Stanley Brunn Award for Media Geography. The work was published in Aether: The Journal of Media Geographer, in 2010. The normative ideas of landscape we have are most powerful tools that belie even our best of intentions. During the Indian Removal Period, I found the majority of American public opinion, and the majority of media coverage, to be generally sympathetic to the plight of the Potawatomi and Native Americans in general. Even downright hostile to the Federal Government. However, buried within this seemingly benign and sympathetic discourse were normative ideas of landscape that justified dispossession. Landscape provides a convenient way out of an otherwise impossible moral conundrum: well, it is only natural after all, isn’t it?

Abstract from Aether: Journal of Media Geographies, 8b Fall 2011

In this paper I examine the role of the media in the politics of Indian removal. Specifically, I look at the 1845 negotiations over the Potawatomi reservation in present-day Iowa and their eventual removal to Kansas. Richard Smith Elliott, a former newspaper editor who would go on to become a war correspondent in the Mexican-American War and later one of the chief boosters behind the ―rain follows the plow‖ idea in western Kansas, became an advisor for the Potawatomi in negotiations with the federal government. As anthropologist James Clifton (1977, 331) wrote of the Potawatomi and Elliott: ―by the fall of 1845 they had invented a professional role new on the American scene. Just ahead of P.T. Barnum, these Indians helped to create the press agent.‖ What is interesting about Elliott and his role in media history is not how he used newspapers to directly influence public policy. Rather, what this history shows is how media are used to obfuscate power relations at work in the formation and implementation of public policy, and role of landscape in discourses of legitimation.

AAG 2008

Great Plains Symposium, 2007